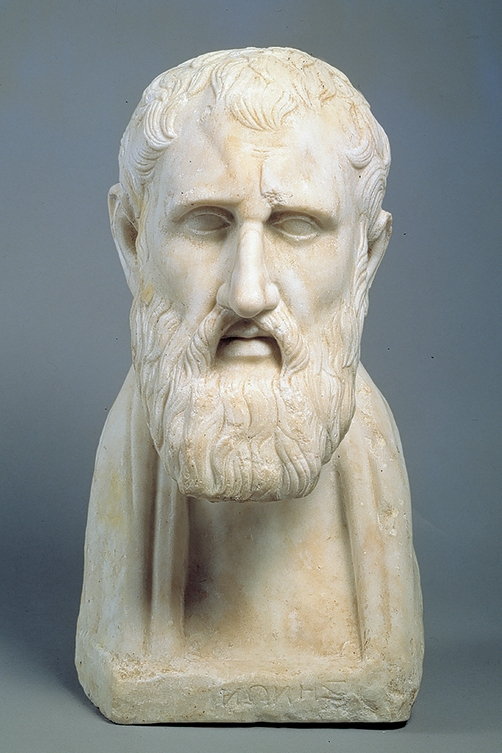

The Hellenistic age was one of specialisation. In the fourth century BC the school of Aristotle had pursued a wide range of scientific and historical studies without fully demarcating these from philosophy proper. The Hellenistic age, which officially starts in 323 BC and thus just a year before Aristotle’s death, was one in which science and philosophy to a large extent went their own separate ways. Although, for example, the heliocentric theory of the astronomer Aristarchus shocked the Stoic Cleanthes (331/330–232/231 ca.), and although the scientist Eratosthenes (276/272–196/192) had a philosophical training in Stoicism, interaction between the two disciplines was in general minimal. Alexandria, the great new cultural centre of the Greek-speaking world, attracted most of the leading scientists, who depended on the patronage offered by the Ptolemies’ regime. Philosophy, on the other hand, stayed rooted in Athens, its ancestral home since the age of Socrates (469–399), who himself remained a major figurehead for philosophical movements. It was at Athens that the two major new doctrinal schools were established and flourished: the Stoa, founded by Zeno of Citium (334–262), and the Epicurean Garden. And it was at Athens that Chrysippus (ca. 280–206), the most illustrious of Zeno’s successors, developed Stoicism into a truly all-embracing philosophical system.

Alongside them the Academy, founded by Plato (ca. 429–347), continued to be influential throughout most of the Hellenistic age (which officially ends in 30 BC with the start of the Roman empire), although it virtually vanished as an institution after the 80s BC. The real Hellenistic importance of the Academy begins in the 260s, when, under its new head Arcesilaus (scholarch ca. 268–242), its official stance changed from the defence of doctrinal Platonism to the practice of a dialectical scepticism, targeted on the other schools. This New Academy will feature occasionally in philosophical debates on scientific issues. Far more important today, however, are the sceptical critiques of the Pyrrhonist sceptics, whose movement (officially a revival of the early Hellenistic sage Pyrrho) began only in the closing decades of the Hellenistic era. We are fortunate to possess extensive writings by its later representative Sextus Empiricus, himself a doctor and a tireless critic of Stoic and other doctrines.

Physics (physiké), as understood by the philosophers, was a speculative rather than empirical discipline, the study of Nature (physis). Nature itself is conceived by the Stoics as a universal rational principle governing all change. The ultimate goal of studying nature is ethical – to enable the philosopher to live on truly harmonious terms with the world. The goal of life is defined as “living in agreement with Nature”, and this makes the understanding of nature integral to human happiness.

At the lowest level of analysis, the Stoic world is analysed into two ultimate principles – a passive one called matter, and an active one, which shapes and changes it, called god. However, these are purely theoretical constructs, below the level at which observation is possible. Therefore the real focus of Stoic physics comes to lie at the next level up, where out of matter and god are formed the four elements: earth, water, air and fire. These are the protagonists of observable processes of cosmic change. Earth and water are treated as playing a primarily passive and material role, while air and fire are active. Severally or, more usually, in combination, air and fire constitute the “breath” or pneuma which inform the two passive elements and shape them. Thus, at the level of the four elements, the two active ones play a role analogous to that of “god” at the lowest level, while the two passive ones play a role analogous to that of “matter”.

The idea of pneuma as a vital force was of medical origin, but through the influence of Stoicism acquired a pervasive influence in ancient thought, including theology. “Creative fire” (pyr technikón), the most divine manifestation of this active element, is often identified with Nature. Nature is variously defined, for example as “creative fire methodically proceeding (odõ badízon) to generation” (Diogenes Laertius, VII, 156), or as “A state which moves itself in accordance with seminal principles (spermatikoi lógoi), bringing about and holding together its products in defined periods of time and making them of the same kind as their parents” (ibidem, VII, 148). These and other definitions seem to be neutral as between “universal Nature” and “individual Nature” – a pair of concepts which were separated mainly for ethical purposes when Stoics sought to clarify their ethical ideal of “living in agreement with Nature”.

To the Stoics, the crucial importance of this pneuma is that it serves as the vehicle for the divine intelligence which pervades the cosmos and governs it for the best. Although all-pervasive, pneuma varies in its degree of “tension”, and those variations divide it into three kinds. At its least refined, it is the “state” or “tenor” (héxis) which binds discrete physical objects together as cohesive entities, identifiable also with whatever physical qualities they may have. At a level of higher refinement, pneuma becomes the “Nature” (again physis, but here used in a specialised sense) or life force of a living thing, identifiable with its basic vegetative qualities. Finally, at the highest level of refinement, pneuma is “soul” (psyché), the cohesive set of vital properties which is unique to animal organisms. In addition to individual animals, the world itself taken as a whole is a perfectly unified living creature with its own soul. The complete physical permeation of the world by pneuma requires the total interpenetration of two substances – a possibility which Stoic physics defends, and which relies ultimately on their further thesis that body (like space) is infinitely divisible.

The Stoic endowment of the entire world with divine rationality is accompanied, at first sight surprisingly, by the physicalist thesis that all existing things are bodies. Only bodies have the power to interact, a power which even the divine pneuma must share if it is to possess causal efficacy in the world. Stoic physics does not reduce intelligence to a set of merely corporeal qualities. Rather it insists that, along with its irreducible vital and intelligent powers, pneuma must also have the bodily features of three-dimensionality and resistance if it is to be efficacious in moving material objects. The same applies to the vast majority of supposedly abstract qualities and entities. By use of a special system of categories, these are reclassified as bodies in a certain state. For instance, virtue is the rational mind in a certain state, the rational mind itself being part of the soul, which in turn is a portion of pneuma and hence a body. The only incorporeals in the Stoic world are time, place, void and the lektón; this last is, roughly speaking, the signification of a sentence or of certain of its parts. For the purposes of this chapter, it is important to note that logic is viewed as a set of relations between lekta. These are conceded to play no interactive part in the world, but, somehow, to constitute a conceptually indispensable background to it.

The Stoic cosmos has a fixed life-cycle, ending in total conflagration (ekpírysis), which as pure “creative fire” represents its most perfect state of divinity. From this uniform fiery mass there emerges in time a new cosmos, identical to the old in every detail: this being the best possible world, any change would be for the worse. There follows the process of cosmogony, in which the fiery stuff stratifies itself into the four elements, already containing in itself the “seminal principles” (spermatikoi lógoi) from which all life forms will eventually emerge. The Stoic world is thus one which (a) recurs in an eternal cycle, and (b) is entirely predetermined. God, acting as the immanent universal cause, providentially plans and enforces every detail from first to last.

Even regardless of divine providence (prónoia), the causal nexus (heimarménē, “fate”) is in any case all-embracing, according to Stoicism, since to deny this would be to breach the fundamental law that nothing happens without a cause. Stoic causal theories, which in turn strongly influenced medical causal terminology and theory, distinguish many kinds of cause. Of these the most important pair are the “primary” (principalis) and the initiating (“procatarctic”) cause, of which the former is chiefly responsible for the effect but relies on the triggering action of the latter. For example, if a cylinder rolls on level ground, its shape is the “primary” cause of the rolling, but an initiating push, needed in order to start the process, counts as the “procatarctic” cause of that same effect. An alternative pair of causes was a “complete” or “self-sufficient” (autotelés) cause, accompanied by an “auxiliary” (synergon) cause which, while not necessary to the operation of the former, intensifies its effect. Thus if a cylinder is rolling downhill, its shape is this time the “complete” cause of its rolling – a cylinder will always roll downhill unless positively impeded – but, since if someone pushes it it will go faster, that push may still count as an “auxiliary” cause of its rolling.

Being imbued with divine rationality, the world itself in a way is identical to god. Proving the existence of god is the same activity, for the Stoics, as proving that the world is perfectly rational. With this end in view, the Stoic theological arguments, of which many survive, develop in particular the following themes:

- (a) According to the argument from Design, the world is like a giant mechanism; if any man-made mechanism must have an intelligent designer, e.g. the working planetarium built by Archimedes, so a fortiori must the cosmic mechanism itself, the one which Archimedes was merely imitating;

- (b) The world is full of beneficial structures which we have not ourselves invented, e.g. the cycle of seasons, or the pig (a walking foodstore, providentially created alive in order to keep the meat fresh);

- (c) The world is so beautiful that it can only be the work of a consummate artist;

- (d) The apparent imperfections cited by critics of this theological view are either blessings in disguise – e.g. wild beasts to encourage the acquisition of bravery – or unavoidable concomitants of good structures, e.g. the fragility of the human skull;

- (e) It is laughably improbable that such a world might be, as the Epicureans claim (see section 3), the result of mere accident.

In developing a theory of scientific inference, the Stoics were above all aiming to impose a formal structure on arguments of the above kind, ones which serve to reveal the hidden nature of the world. The supposition of the world’s intrinsic rationality encouraged the expectation that its structure would become fully intelligible once it was mapped onto the relevant logical chains of reasoning. This involved the following tasks:

- defining a scientific “demonstration” as a certain type of argument which proceeds from previously known premises to a previously unknown conclusion;

- constructing an epistemology which justifies the thesis that the premises of such proofs can be evident and known;

- establishing and justifying the logical force of the connexion between premises and conclusion.

A demonstration (apódeixis) is “an argument which through agreed premises by means of deduction reveals a non-evident conclusion” (Sextus Empiricus, Pyrrhoneion hypotyposeon, II, 135–143). That the premises must be “agreed” reflects the dialectical nature of all Stoic logic – it is always envisaged as taking place in a question-and-answer format and thus drawing on a respondent’s existing knowledge. Hence the “agreed” premises are taken to be “evident”, or more correctly “pre-evident” – known in advance. The conclusion, equally, must not be pre-evident, or it could not remain to be revealed by the argument. Hence the standard Stoic syllogism, “If it is day, it is light; but it is day; therefore it is light”, although valid, is not a demonstration, since its being light is as pre-evident as its being day.

A further requirement is that assent to the premises must genuinely be the reason for one’s subsequent assent to the conclusion. It is not enough to supply suitable premises in retrospective justification of a conclusion which one already accepts for other reasons. The example quoted (ibidem, 141) is of producing a syllogism to justify trust in a god’s promise, when in fact one already trusts the god’s promise out of memory and habit. A scientific demonstration, by contrast, must be genuinely enlightening.

Next, it needs to be explained how there can be pre-evident premises. These divide into truths which are directly and unmistakably observed, and those which are conceptually self-evident. A premise obtained by direct observation is the content of a “cognitive impression” (phantasía katalēptiké; also variously translated as “apprehensive presentation”, etc.). An impression (phantasía) is a state of mental awareness which presents things as being in such and such a way. A state of belief is attained only when one chooses to “assent” to the impression, i.e. take it to be true. According to the Stoics, some impressions – usually obtained through the senses – are unmistakably true, thanks to a kind of self-guaranteeing clarity which they possess. Unless we are seriously misled by some competing false belief, we cannot but assent to these “cognitive impressions”, which then become the agreed and pre-evident foundation on which scientific inferences may be built. The Academic sceptics’ attacks on the Stoic world-view largely concentrated on exposing the weaknesses in this theory of self-guaranteeing impressions (see especially Cicero, Academica, II, 64–98).

However, in a demonstration at least one of the premises will have a logically complex form which cannot represent the immediate content of a sense-impression. Usually these are conditionals. Indeed, Stoic scientific method is largely articulated in terms of “signs”, a sign itself being defined as “a proposition which is the pre-antecedent [prokathēgoúmenon, apparently a technical term for an evidently true antecedent] in a sound conditional, and which reveals the consequent” (Sextus Empiricus, Pyrrhoneion hypotyposeon, II, 104). Thus the standard form of an inference from signs – which we may take to be itself the normal form of Stoic “demonstration” – is: “If p, then q; but p; therefore q”, where “p” is a pre-evidently true proposition, serving to reveal the truth of “q”.

Possible examples (slightly simplified) of such conditionals from actual Stoic cosmological arguments include: “If there is something which human beings cannot make, whoever made it is superhuman” (Cicero, De natura deorum, II, 16). Such premises acutely raise the question of the criteria by which a conditional can be recognised as a pre-evident truth. Here Stoic logic wavered between two types of solution. Some Stoics – apparently early ones – followed the pre-Stoic logician Philo (fl. c. 300 BC) in adopting a truth-functional account of a sound conditional: the conditional “if p, then q” is true provided only that it does not have a true antecedent but a false consequent. But Chrysippus, whose logic was to become the standard Stoic one, promoted the alternative criterion known as synártēsis (“cohesion”): a sound conditional is one where the negation of the consequent “conflicts with,” i.e. is incompatible with, the antecedent.

The former, truth-functional account authorises a wide range of conditionals to express bona fide signs. A standard example was: “If this woman has milk, she has conceived.” Presumably the reason for taking such a conditional to be true is the prior observation that whenever any woman has milk she has conceived. In other words, this early Stoic account of signs permits inferences from observed data, including many based on nothing more than the observed regular conjunction of two types of event or fact. Such signs came to be known as “commemorative” or “reminding” (hypomnēstiká) signs in the ancient tradition. Whether the Stoics themselves ever adopted this terminology, and recognised these as a bona fide kind of sign, is disputed.

An objection which so generous a notion of “sign” naturally invites is that it may allow many propositions to count as signs whose truth by no means guarantees the truth of their significata. For instance, “If this woman has milk, she has given birth to twins” would be the basis of a true sign-inference, provided only that both antecedent and consequent happened to be true. It is therefore not surprising that Chrysippus insisted that a stronger link than this must be expressed by “if.” On his synártēsis account, the inference from present lactation to past conception would fail, since there is no intrinsic logical or conceptual incompatibility between the propositions “This woman has milk” and “It is not the case that this woman has conceived.” Returning, therefore, to “If there is something which human beings cannot make, whoever made it is superhuman,” a conditional reported to have been used by Chrysippus, he must have maintained – however controversially (what about spiders’ webs?) – that it really is self-contradictory to say of something “No human being could have made this, but its maker is not superhuman.”

In deciding whether such conditionals are sound, the Stoics’ regular criterion of truth was prólēpsis, inadequately translated as “preconception.” This is the natural generic conception of a thing, whether founded on sensory experience or on our innate moral dispositions. Because they are uncontrived and, supposedly, shared in common between all human beings, prólēpseis can provide us with the parameters against which to judge what is intrinsically necessary or possible. For example, the prólēpsis of “solid” may inform us that liquids cannot flow through solids, and thus can help establish the sound conditional: “If sweat flows through the skin, there are invisible pores in the skin” (Sextus Empiricus, Pyrrhoneion hypotyposeon, II, 142).

Signs understood as relying on so tight a form of implication came to be known as “indicative” (endeiktiká) signs, by contrast with “commemorative” signs. Again, it is disputed whether the distinction was one which the Stoics themselves adopted. One illuminating way in which the distinction was explained (ibidem, 97–98) is as follows. Of non-evident things, some are “absolutely” (kathápax) non-evident, e.g. whether the number of stars is odd or even; some are “temporarily” (pròs kairón) non-evident because of circumstances; and yet others “naturally” (phýsei) non-evident, for example microscopic pores in the skin, whose existence can be inferred, e.g. from the passage of sweat, but not directly observed. The absolutely non-evident things are not the subjects of sign-inferences at all. The temporarily non-evident things may be revealed by “commemorative” signs; but it is only the “naturally” non-evident things that may be revealed by indicative signs. An indicative sign is one which “from its own nature and structure signifies that of which it is a sign, in the way in which bodily changes are signs of the soul” (ibidem, 101). There is little doubt that in their inquiries into Nature it is this latter kind of sign – whether or not so named – that preoccupied the Stoics. Discovering the divine causation behind the world’s structure is a matter of just this kind of inferential inquiry.

The conditional is the most potent single logical component of these scientific inferences, but the whole of Stoic logic was brought to bear on the same task. The basic units of Stoic logic are simple propositions, which are combined to produce complex propositions. These latter are comprised of not only the conditional, but also the disjunction (“p or q”) and the conjunction (“p and q”), whose most common use is in the form of the negated conjunction (“not both: p and not-q”). An example of an elaborate pair of Stoic syllogisms which combines conditionals, disjunctions, and negated conjunctions is the following argument of Chrysippus, invoked to demonstrate the existence of divinatory signs:

I.

- If there are gods but they do not indicate future events to mankind in advance, either they do not love mankind, or they are ignorant of what will happen, or they think it is not in mankind’s interests to know the future, or they think it beneath their dignity to give signs of future events to mankind in advance, or even the gods are unable to give signs of them.

- But neither do the gods not love us (for they are beneficent and friendly to mankind); nor are they ignorant of what they themselves have set up and ordained; nor is it not in our interests to know future events (for we will be more careful if we know); nor do they think it foreign to their dignity (for nothing is more honourable than beneficence); nor are they unable to foreknow future events.

- Therefore it is not the case that there are gods but that they do not give signs of future events.

- But there are gods.

- Therefore they do give signs of future events.

II.

- And it is not the case that if they give signs they give us no routes to scientific knowledge of sign-inference (for in that case their giving signs would be pointless).

- And if they give us the routes, it is not the case that divination does not exist.

- Therefore divination exists.

(Cicero, De divinatione, I, 82–83)

This kind of complex syllogism lies at the heart of Stoic scientific speculation. A major concern of Stoic logic was therefore to establish the formal validity of such inferences. The starting point was the listing of five “indemonstrable” arguments, regarded as the irreducible building blocks of all other arguments, which were themselves to be proved valid by reduction to one or more of the indemonstrables. Four rules, known as thémata, were employed for the purposes of such reduction. For convenience, the following list of the indemonstrables borrows the Stoic device of replacing atomic propositions with ordinal numerals:

- If the first, the second. But the first. Therefore the second.

- If the first, the second. But not the second. Therefore not the first.

- Not both the first and the second. But the first. Therefore not the second.

- Either the first or the second. But the first. Therefore not the second.

- Either the first or the second. But not the second. Therefore the first.

A conjunction is treated as truth-functional: that is, its truth value is determined purely by that of the individual conjuncts. Thus the negated conjunction, as in 3, came to replace the “Philonian” conditional (see above) in Stoic logic. The grounds for affirming a negated conjunction might vary considerably. Chrysippus (Cicero, De fato, 15) thought it, rather than the conditional, to be the appropriate formulation for an astrological law, such as “If x was born at the rising of the dogstar, x will not die at sea.” This was presumably because such laws become credible (if at all) through the empirical generalisation that no one born at the rising of the dogstar ever dies at sea, which neither implies nor requires any conceptual link between the two conjuncts. But in other cases a negated conjunction might well be arrived at by purely conceptual considerations – as, for example, in I c) of the above pair of complex syllogisms.

A conditional on the other hand came in time, as we saw earlier, to be treated by Stoic logicians as non-truth-functional: its soundness is determined by the relation between its two component propositions, regardless of their individual truth values. The same is the case for disjunctions, as in 4 and 5. Stoic logic is unusual in requiring that any pair of disjuncts must be so related that necessarily one of them is true, the other false. (This raises a considerable problem about how to analyse multiple disjuncts, as in I a) above.)

The Stoics’ use of these inferential schemata occurs mainly in the furtherance of their own philosophical agenda: proving the divinity and rationality of the world, the all-embracing character of the causal nexus (or “fate”), the nature of the good, etc. Only occasionally are they found trespassing on the territory of the professional scientists. One rare such case is their clash with the medical profession over the location of the hēgemonikón, the “commanding-faculty” of the soul.

The Stoics frequently came under attack from their main contemporary critics, the sceptical New Academics, in matters of scientific concern. A particularly deadly weapon employed by these critics was the sorites, or heap argument. How many grains make a heap? If two do not, surely three do not either, or four – and so on by gradual increments to the absurd conclusion that even ten thousand grains do not make a heap. Such “little by little” arguments challenge an opponent to find a precise cut-off point between two contrary properties. They were used to attack many of the distinctions which the Stoics regarded as fundamental to their analysis of the world, including in particular that between the divine and the non-divine. If a cosmic mass like the sea (equated with Poseidon) is divine, so too are rivers, streams, and so on, all the way down to puddles of water. Where can the Stoics draw the line? Cicero, on behalf of the New Academy, generalises the scope of such attacks:

Nature has permitted us no knowledge of limits such as would enable us to determine, in any case, how far to go. Nor is it so just with a heap of corn, from which the name [“sorites”] is derived: there is no matter whatever concerning which, if questioned by gradual progression, we can tell how much must be added or subtracted before we can give a definite answer – rich or poor, famous or unknown, many or few, large or small, long or short, broad or narrow. (Academica, II, 92)

Chrysippus, in defence of Stoicism, wrote a number of books (all now lost) attempting to solve the sorites. Only a little can now be recovered of Stoic solutions to it. It is certainly significant that the regular Stoic practice was to reformulate sorites inferences so as to redefine their logical force. Instead of the conditional, e.g. “If n are few, then n+1 are few,” used by their Academic opponents, Stoics normally insist on the “negated conjunction” “Not both (n are few and n+1 are not few).” This is reminiscent of Chrysippus’ insistence (see above) on the same reformulation for astrological laws, and implies a recognition by the Stoics that no actual incompatibility would be involved if, say, 6 were few but 7 were not few. A possible inference is that, in their view, there really are precise cut-off points of this kind in the nature of things, even if it may sometimes be beyond human capacity to identify them. This last supposition might, in turn, account for the tactic, reportedly recommended by Chrysippus, of simply refusing to answer any further questions once the sorites reaches the borderline cases.

We will return to the Stoics below (section 4). But for the present we may conclude with a glance at their conception of science itself. Here the fundamental term is téchnē, an “expertise” or “skill.” Expertise as such is the state of mind possessed by the expert, and is defined as “a state (héxis) which advances methodically with impressions.” The curious addition “with impressions” was made, we are told, to distinguish human expertise from Nature itself, which is also a state – of the world – that advances methodically, but without the “impressions” (primarily sensory) which characterise human understanding. On the other hand, an expertise is a body of knowledge, potentially shared between many individual experts. It is defined as “a systematic collection of cognitions unified by practice for some goal advantageous in life.”

“Science” (epistēmē) differs from mere expertise in that any human being may possess an expertise, in greater or lesser degree, whereas “science,” properly understood, is the perfect grasp of a subject found only in the wise (a vanishingly small group of people, as the Stoics were forced to admit, and important to them more as a paradigm than as a reality). Only the wise have “science,” because only they possess a complete and mutually supporting set of cognitions which jointly preclude the possibility of error.

The requirement that a science – whether a mere expertise or a “science” in the strict sense – must be “for some goal advantageous in life” is fundamental to Stoicism. There are no absolutely “pure” sciences. The skills which are integral to philosophy, including physical and dialectical science, are all valued ultimately as contributions to a good life. The most fundamental science of all, in fact, is moral virtue, which is viewed as a set of skills founded on theorems, rules and other principles no less than, say, medicine or astrology is. This can be seen as a development of Socrates’ thesis that virtue is “knowledge” (also epistēmē). Unlike medicine and astrology, however, virtue is a “science” only, in the narrow Stoic sense, and never a mere expertise. You can be better or worse at astrology or medicine, but not at moral goodness: someone who is worse than another at being just or brave is not just or brave at all, on the Stoic analysis, but on the contrary unjust and a coward.

The rejection of pure sciences may help account for the otherwise surprising lack of attention on the part of the Stoics to the philosophy of mathematics. Early Stoic interest in geometry, for example, seems to have been almost entirely limited to resolving the problems of the continuum, by defending, against the critiques of Zeno of Elea and the Epicureans, the mathematical coherence of the infinite divisibility of magnitude (Plutarch, De communibus notitiis contra Stoicos, 1078e–1080e; Sextus Empiricus, Adversus mathematicos, X, 121–126; 139–142). It was only with the later Stoic Posidonius (see below) that the mathematical sciences were reintegrated into the philosophical curriculum.

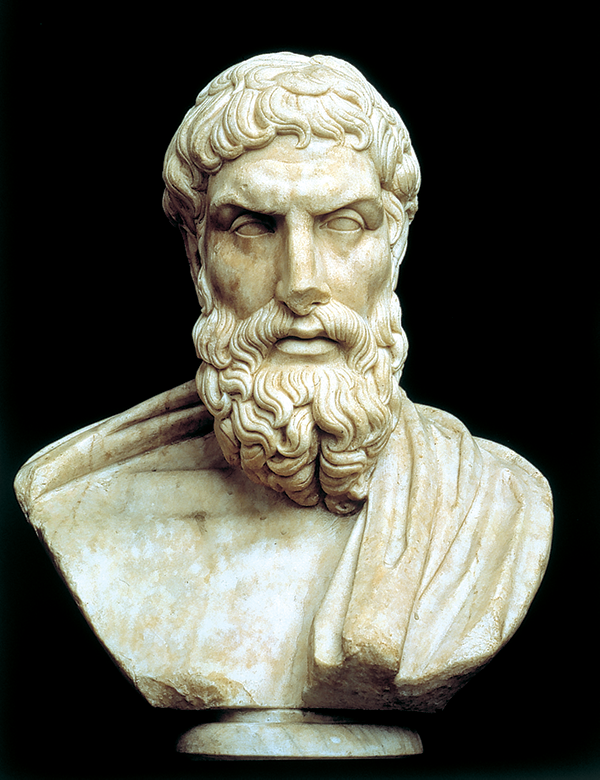

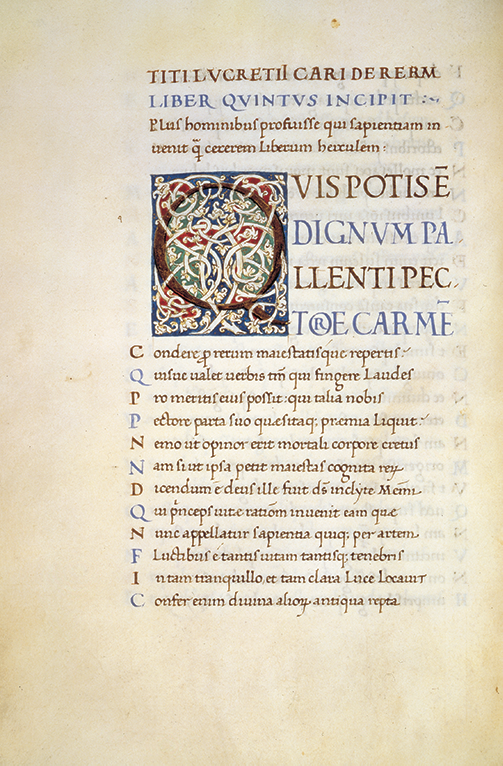

Epicurus (341–271 BC) founded a philosophy which was to remain influential in the Greco-Roman world for five or more centuries. It emerged from the early atomist tradition, whose main figure was Democritus (mid to late 5th century BC), but modified that system in a number of significant ways. Unlike Democritus, we actually possess some complete Epicurean texts on physics, enabling us to reconstruct in detail the principles and practices of Epicurus’ scientific method. These are Epicurus’ two physical epitomes – the Letter to Herodotus and Letter to Pythocles – and the brilliant Latin poem of Lucretius (ca. 94–55 BC), De rerum natura.

Epicurus’ physics analyses the world from the bottom upwards. A mixture of immediate empirical data and primary intuitions is invoked to establish that (1) the world has permanent constituents; (2) nothing exists but body and space; (3) space is, in its own nature, pure vacuum, even though parts of it are at times occupied by bodies; (4) there must be microscopic portions of body, unpunctuated by vacuum, which are completely solid and unbreakable, in fact “atomic”; (5) these atoms, infinitely many of them moving perpetually in infinite space, are sufficient to generate out of their arrangements both our world and infinitely many others, including their contents such as the soul and all mental and phenomenal properties. It is this postulation, in a world without microscopes, of an entire realm below the threshold of sense-perception that compels atomism to develop a highly articulated methodological base. A further feature which helps to characterise Epicureanism’s distinctive scientific outlook is its determination to exclude all divine causation from the world, by finding naturalistic explanations for all phenomena.

The most important Epicurean innovations, by comparison with the earlier atomism of Democritus, are the following. First, where Democritus seems to have left it obscure whether atoms, while themselves unbreakable, have mathematically distinct parts, Epicurus is very explicit on the point. Atoms, which vary in shape and size, are the smallest units into which body can actually be fragmented. But an atom is itself analysable into a finite set of smaller units. The unit in question is mathematically the absolute smallest magnitude, known as the «minimum in the atom». The need to posit such a minimal magnitude – that is, to insist that magnitudes are only finitely divisible – arose from the famous paradoxes of Zeno of Elea, who had argued that in an infinitely divisible continuum any magnitude, however small, would consist of infinitely many parts and therefore be impossible to traverse in a finite time – as well as possibly proving to be infinitely large.

Second, the rigid causal laws of Democritean atomism, whereby every motion of every atom is determined by its physical properties, its present trajectory, and the inevitable collisions into which this leads it, were held by Epicurus to make the human mind itself a mere automaton, incompatibly with the evident fact of our rational autonomy and moral freedom. He therefore concluded that there must be a minimal degree of indeterminacy in the motions of atoms, known at parénklisis (“swerve” or “deviation”), whereby they may unpredictably shift from their current track to an adjacent one. The hypothesis that atoms do so deviate is argued to be necessary if atomism is to be compatible with the facts of human experience, and at the same time compatible with the orderliness of the natural world, since a minimal deviation would be insufficient to generate macroscopic chaos.

Third, since vacuum can offer no resistance to them, all atoms move perpetually and at equal speed. It is the relative density of the medium, like air or water, that causes macroscopically moving objects to vary in speed, whereas vacuum has zero density. In inter-cosmic space, atoms naturally move downwards under their own weight (“down” being a universal direction, not as the Stoics and others held one relative to the centre of our own world). When a large number of atoms collide (thanks to random “swerves” as they fall parallel to each other) and form a complex arrangement like our world, they continue to move at their regular speed in the vacuum, but now do so in complex patterns of motions involving regularly repeated collisions.

Fourth and last, Democritus had concluded that phenomenal qualities like colour are not part of the objective nature of things at all, but mere impressions generated by interaction of atomic structures with our sense organs. Epicurus agrees that atoms themselves are not coloured, flavoured etc., but he insists that such properties are entirely real, albeit at a different level of reality. Thus where Democritus’ findings had pointed towards scepticism about the possibility of relying on the senses, Epicurus is able to argue that the data of the senses gives us genuine access to one kind of reality, from which we may proceed, with caution, to infer downwards to the nature of the phenomenal world’s microscopic constituents. This is the foundation of his scientific method.

Epicurus is not content to assert, in general terms, that the senses constitute a reliable basis for scientific inference. His controversial dictum on the matter is that “all sensations are true”: there are no illusory sensations at all. The scientist’s inferential procedures do not start from a decision which sensory data to trust and which to reject, but rather from the task of discriminating just what may and what may not be legitimately inferred from them in each case. At an extreme, even the sensations experienced in dreams count as “true,” but what can be inferred from them about the external world is of course severely limited.

The sensations which are guaranteed true are reports of the primary representational contents of sense experiences, e.g. the registering of a red circular colour patch or a pungent smell, and not the propositional judgment based on them, e.g. that the Sun is setting or that someone needs a bath. The most helpful way for us to think of their “truth” is by a photographic analogy. The image on a photograph may well fail to correspond to the shape and other features of the object represented, but may still be called “true” in that it is an objective registering of the pattern of light waves arriving at the lens, without the imposition of any interpretation by the photographer. The photograph thus constitutes bona fide evidence about the external object, and as far as it goes it is veridical. If a photograph misleads, that is because of the faulty inferences founded on it, but in itself “the camera cannot lie.” With Epicurus’ theory likewise, it is crucial to appreciate that the “truth” in question is representational, not propositional.

All sensations are explained by the arrival of atomic matter from outside (analogous to the light waves in the photographic parallel). In vision, the paradigm case of sensation, this atomic matter comes in the form of streams of “images” (Greek eídüla, Latin simulacra), which are the atomic surface layers of compound bodies, constantly discharged at high speed in all directions. These enter the eye and cause vision. Also – when mental visualisation occurs, as in dreams and imagination – very fine ones may directly enter the mind through “pores” in the body. The representational “truth” of our visual impressions is, as regularly in Greek thought, truth about the external world; but it lies in the fact that they accurately report, not the properties of the solid object seen, but the state of the images from it at their moment of arrival at the eye. This allows for the images’ distortion by the distance travelled and the density of the medium through which they pass, without diminishing their truthfulness. When you see a hazy shape in the distance, or a straight oar looking bent in the water, you are accurately registering the images as they are when they reach your eye. As Epicurus in effect argues (Sextus Empiricus, Adversus mathematicos, VII, 208), if someone were to object that for vision to be true it would have to register the distant object exactly as that object itself is, this would be as implausible as to claim that you can only correctly hear someone speaking when you hear the sound of their voice as it is inside their larynx!

But even on this rather plausible conception of perceptual “truth,” how can Epicurus be confident that there are no false sensations, ones which simply fail to correspond to anything external at all, or to represent correctly the images causing them? He anticipates this danger by appeal to a purely a priori argument for the truth of all sensations. That all sensations are true is established by excluding the two alternative possibilities, (1) that all sensations are false, and (2) that some sensations are true but others false. The objection to (1) is that it would leave us with no access to truth at all – not even by use of reason, which is impotent without the support of sensory information. Thus (1) amounts to absolute scepticism, a position which is alleged to be self-refuting: not only is it unlivable in practice, but it cannot even be coherently avowed, since its proponent has to relinquish any claim to understand such fundamental epistemic notions as true and false, certain and uncertain. As for (2), the objection to it rests on the sheer arbitrariness of any attempt to distinguish false sensations from true ones. How could a sensation be refuted? Only by the senses, on which all processes of reasoning depend. But one sensation could not refute another, since if two sensations conflicted it would be entirely arbitrary to select one of them as the true one and the other as false. Besides, a little further reflection shows that sensations never do conflict. No one sense ever conflicts with another, since each reports primarily on its own special objects, which it does not share with any other sense. Hearing cannot challenge vision’s reports on colour, or vision challenge hearing’s reports on sound. Even such “common” perceptual objects as shape are not, strictly speaking, matters for disagreement between the senses, since vision reports the shape of a colour patch, touch the shape of a solid body, and in most viewing conditions there is no reason why these need be identical. Even separate sensations by a single sense organ cannot conflict, since they all start out with equal status in reporting on their own respective immediate objects.

Falsity, then, is not a property of sense-impressions themselves. It enters the story only at the level of “added opinion” (tò prosdoxazómenon), whereby perceivers interpret their primary data. However, one of the hazards faced by an Epicurean empiricist, as Lucretius warns us (IV, 467–468), is that it can be extremely difficult to distinguish a pure sense-impression from an impression already interpreted by the mind. What we think of as self-evident may in fact already contain a component of judgement. This warning highlights the empiricist’s first task in the business of scientific inference – deciding just which data are guaranteed by sense-perception.

But when we turn to the surviving Epicurean theory and practice of scientific inference, considerable unresolved problems become apparent. We are told that all inference must proceed from what is perceptually self-evident, and Epicurus’ first examples of such premises include the assertions (1) that bodies exist, and (2) that they move. Now (1) seems unobjectionable, since body is itself the direct special object of the sense of touch. But (2), that bodies move, is surely not directly given by any sense. Should Epicurus not admit that it is an inference from the differences that we notice between successive sense-impressions. Moreover, as Lucretius (in Book IV) eloquently points out, there are many illusions in which things appear to be moving when in fact they are not, both in waking life and in dreams. Strictly, then, the empirical data about the world on which Epicurean scientific inferences rely will frequently be, not the contents of sensations as such, but interpretations of those contents – that things move, that spherical objects move more smoothly than jagged ones, that all compounds are dissoluble, that falling objects move in parallel trajectories, etc. These are in principle fallible judgements, and when they are treated as indubitable empirical truths by the Epicureans we must assume that they have acquired that status by means of rational evaluation, testing, generalisation etc. The thesis that all sensations are true does not in itself guarantee these empirical premises; rather, it provides, in the face of the sceptical challenge, a reassurance that we have at our disposal the necessary criteria for confirming their truth.

Starting from these empirically well-founded premises, Epicurean physics constructs numerous inferences to establish “non-evident” conclusions. All sign-inferences (sämeióseis) are from the evident to the non-evident (cf. the Stoic account, above). Those (a) from the macroscopic to the microscopic are frequently (c) causal, i.e. inferences from an evident effect to its microscopic cause. Typical examples are the inference from the observed regularities of natural processes to the existence of unchanging primary elements (Lucretius, I, 149–264), or from the evident fact of human psychological autonomy to the existence of indeterminacy (the “swerve”) in the motions of our constituent atoms. The notion of “cause” is not itself theorised in our surviving Epicurean texts, and the atomic causes of macroscopic phenomena are likely to amount in some cases to necessary conditions of their realisation, in others to sufficient conditions.

More fundamental to Epicurean methodology are (d) analogical inferences from the evident to the microscopic. A simple case is the determination of atomic shapes: if the atoms constituting liquids are judged to be smooth-shaped, while those constituting sticky substances are taken to be hooked and irregular, these are simply analogical inferences from the observed behaviours of objects with those respective shapes at the phenomenal level. A more complex and demanding example of (d) is the analogical argument in support of the thesis (see above) that there is a smallest magnitude. Aristotle had bequeathed the problem that minimal and hence partless magnitudes, if they existed, could not be adjacent to each other as they would need to be if larger magnitudes were to be formed out of them: they could touch neither part to part (since they would not have parts) nor whole to whole (since that would make them coextensive, not adjacent). Epicurus’ answer (Ad Herodotum epistula, 58–59) starts from an analogous phenomenon, the “minimum in sensaton,” i.e. the smallest magnitude you can see. Any larger visible magnitude may be analysed into a series of such visible minima, and these will be seen in an ordered sequence whose individual member touch each other neither part to part (since they have no visible parts) nor whole to whole. Hence there is a way of being adjacent which Aristotle’s dilemma overlooked, and sub-atomic minima may be in contact in that way. This analogy does not prove the existence of absolutely minimal magnitudes – that is established earlier, on purely theoretical grounds, by appeal to Zeno’s paradoxes of infinite divisibility – but it does confirm that such minima are, pace Aristotle, capable of being juxtaposed to constitute larger magnitudes.

In both the above examples, then, analogical inference from the macroscopic to the microscopic is a powerful tool for uncovering the nature of atomic and sub-atomic structures. Equally important, in other contexts, is (b), inference to macroscopic truths which are not directly open to inspection. Among these, both (e) inductive inferences and (h) inferences about the past and future are ubiquitous in Epicurean texts, although they are not treated theoretically by any surviving Epicurean, apart from Philodemus’ defence of analogy, which will be considered separately below. The numerous Epicurean inductions include the generalisations that all compounds are dissoluble, and that unobstructed bodies naturally move downwards. It is probable that these kinds of judgement were grouped by Epicurus under the name epimartìräsis, “attestation,” meaning that they are capable of positive confirmation, by contrast with ouk antimartìräsis, “non-contestation,” which is invoked (see below) for findings about matters that fall outside the range of direct experience. As for inferences from the present to the past or future, these may be causal (from present effects to past causes, or from present causes to future effects) or analogical (e.g. from biological generation as it is now to the origin of life, or from the dissolubility of all present compounds to the future destruction of the world).

The special importance of inferences about the past lies in the Epicurean commitment to opposing teleological explanation: if the origin of the world itself, and of human institutions like language and law, is not the outcome of divine benefaction, the possibility of their natural generation by a sequence of accidents must be demonstrated from presently available data. However, once again these classes of inference, although widely used, are not explicitly discussed in our surviving Epicurean texts. The class of inference which does receive a full theoretical explanation and defence is (g), that from familiar natural processes to analogous processes in parts of the world inaccesible to direct inspection. These explananda, jointly known as tà metéüra, are above all the motions of the heavenly bodies, but also atmospheric phenomena such as thunder and lightning, and even terrestrial explananda like earthquakes, volcanoes and lodestones. These were traditional puzzles set for Greek physicists to solve, but their special importance to Epicurus lay in the fact that they, more than anything else, were viewed popularly (and even by many philosophers) as clear evidence of divine intervention in our world. Therefore Epicurus’ leading task is to show that all these items are in principle capable of naturalistic explanation. The conclusion that they are in fact not divinely caused depends on separate arguments, in particular that world government is incompatible with the blessed nature of true divinity. But that argument is impotent unless it can be shown that non-divine explanation is at least possible. And it is here that one of the most prominent features of Epicurus’ methodology is brought into play. The principle in question is that of ouk antimartìräsis, “lack of counter-evidence,” or “non-contestation.”

Epicurus’ initial insight is that theories explaining inaccessible phenomena cannot be directly established by empirical means, so that the failure to find counter-evidence to them is the best, indeed the only, method of confirming them. Now Epicurus’ predecessors, especially in the Presocratic era (6th–5th century BC), had come up with numerous physical explanations of the phenomena in question. Epicurus finds that, on examination, nearly all of these pass the test of consistency with familiar and testable phenomena. For example, what causes thunderbolts? Epicurus summarises the possibilities as follows:

It is possible for thunderbolts to occur (a) through multiple gatherings of winds, followed by whirling and a fierce conflagration, with a part breaking off and hurtling even more fiercely into the region below, its breaking off being caused by the greater density of the neighbouring region because of the compacting of clouds; and (b) through the actual fall of whirling fire, in the way in which it is possible for thunder to come about, when the fire increases and is more fiercely fanned and breaks the cloud because it cannot retreat into the neighbouring region since they are all compacted against each other; and (c) it is possible for thunderbolts to be caused in numerous other ways. Only let myth be excluded, as it will be, provided that one makes one’s sign-inferences about non-evident things by properly following the lead of those things which are evident. (Ad Pythoclem epistula, 103–104)

This admittedly difficult set of explanations is intended by Epicurus only as an aide memoire to readers who have already studied his fuller account (sadly now lost). But from the longer, and partly different, account in Lucretius (VI, 219–422) something can be recovered of the “evident” things from which the sign-inference can be made. For example, that wind might itself produce fire, as in (a), is confirmed by the reportedly familiar phenomenon of a lead projectile being heated through air friction, and by the production of sparks from flint and iron (VI, 300–322). Equally, it is clear from Epicurus’ wording in (b) that he has in mind partly the familiar fanning of flames in a furnace. As for the exclusion of myth, at the end of the passage, Lucretius indicates the sort of consideration that Epicurus has in mind, when he observes that thunderbolts can hardly be the gods’ expressions of anger, or they would not hurl them so indiscriminately, wasting many on uninhabited places, and sometimes striking their own temples (VI, 379–422).

Now these multiple explanations might give the impression of being alternative possibilities, with the implication that only one of them can actually be true. However, Epicurus is at times quite explicit that the method used here establishes truths, not just possibilities, and Lucretius makes it clear that the various explanations of thunderbolts are not mutually exclusive. When Epicurus is explaining a certain type of phenomenon, he has no reason to rule out the possibility that it has different causes on different occasions. However, this is less plausible for so specific a phenomenon as, say, the Sun’s orbit or the phases of the Moon, and here at least his fallback position is the following (cf. Lucretius, V, 526–533). The universe is infinite, containing infinitely many worlds. Therefore any causal process which has been shown, by Epicurus’ method, to be intrinsically possible, must actually occur somewhere in it. Whether all or several causes of the same phenomenon occur in our world, or only one here but others elsewhere, is no more than a peripheral question.

Moving now from celestial phenomena to basic physics, there are certainly cases where a plurality of explanations, all of them «uncontested by phenomena», is taken by Epicurus to be true in its entirety. A clear example is the causes of the “images” (eídüla) which cause vision and imagination. There are many ways in which these are generated, he says, all of them «uncontested by the senses»: they come about not only (1) by being emitted from bodies, but also, for example, (2) by spontaneous formation in mid air (Ad Herodotum epistula, 48). From Lucretius’ fuller account in book 4, we can say that the “non-contestation,” in these two examples, consists partly in (1) the analogy of membranes shed by snakes, new-born calves etc., and (2) the spontaneous formation of clouds into monstrous shapes. Here we can see clearly a case where the existence of familiar analogues for two or more hypothesised explanations of the same explanandum is sufficient to make these explanations not only all possible but also all true.

With this last case, we have moved back from (g), analogical inferences from macroscopic events in our own vicinity to macroscopic events elsewhere, to (d), analogical inferences from macroscopic to microscopic events. Here too, as much as in the study of celestial phenomena, Epicurus proclaims “non-contestation” – or “consistency” with things evident – as his fundamental means of confirmation. However, it is rare in atomic physics for multiple explanations to be permitted, as they were in the above multiple explanation of images. As Epicurus himself observes (Ad Pythoclem epistula, 86), when it comes to the fundamental questions of physics, such as what the elementary constituents of things are, it repeatedly turns out that only one available answer is consistent with the full range of phenomena. All alternative theories, such as the four-element theory adopted in part by the Stoics, can be shown in one way or another to fail the test of consistency with phenomena. That is how the method of non-contestation can, when it matters, be invoked to establish a single exclusive truth.

So far the main features of Epicurus’ scientific method to emerge have been the citation of confirmed empirical data as a basis for inference, and the use of a wide range of inferential processes, of which the most important is that of analogy. Some further features of the method can now be briefly sketched. Beyond consistency with phenomena, conceivability provides a further check. This is not the same thing as imaginability, since atomic speed, for example, is unimaginably fast but can be conceived by analogy with things which we can imagine. What is genuinely inconceivable, and therefore to be excluded, is that an atom should be simultaneously in two or more places (Ad Herodotum epistula, 46–47). An allied criterion – in fact one of the official three Epicurean “critera of truth” (along with sensations and feelings) – is próläpsis, which, much as in Stoicism, is the naturally acquired generic conception of a thing. It is probably to the próläpsis of “incorporeal” that Epicurus is appealing at Letter to Herodotus (67) when he argues that the soul cannot be so characterised, on the ground that incorporeality, properly understood, is conceivable only as a property of vacuum. Here, then, we have two methodological principles which appear a priori in character. However, it is important to recall the Epicureans’ insistence that the mind (psyché) has no truly independent capacities, ones which are not ultimately reliant on the senses.

The Epicureans’ committed empiricism may help to explain their attitude to the mathematical sciences, which they are said to have dismissed as based on false principles. In so far as we can recover their specific objections to these sciences, it seems that the criticisms of geometry included its insistence on there being incommensurable magnitudes, such as the lengths of the side and diagonal of a square. According to the Epicureans’ own postulation of a minimal magnitude (see above), all larger magnitudes must be analysable into an exact number of these minima, and hence commensurable with each other. It appears to follow that, on Epicurean principles, the perfect square is a mathematically impossible figure. This was apparently among the findings of Epicurus’ colleague Polyaenus, himself a former geometer. Some later Epicureans seem to have sought ways of reinstating geometry, or perhaps of developing a non-Euclidean geometry, but we know none of the details.

As for astronomy, Epicurus objected strongly to its mathematicization. In particular, he maintained that that the heavenly bodies have peculiar optical properties, whereby their visible size does not vary with distance: hence his notorious thesis that they are as small as they appear. As a result of this optical peculiarity, no terrestrial perspective could permit correct measurement of celestial orbits. A more ideological motivation for the same dismissal of mathematical astronomy is no doubt to be located in Epicurus’ rejection of the mathematicians’ starting point, that the stars must be expected to exhibit mathematical regularity because they are divine. In Epicurus’ view the mistake of holding the heavens to be divine is the source of most human unhappiness.

From the final decades of the Hellenistic period there survive parts of a treatise attesting a vigorous debate between Stoics and Epicureans on exactly the issues considered above. This is On signs, written by the Epicurean Philodemus (ca. 110–35 BC). The damaged papyrus containing it was discovered at Herculaneum in southern Italy, where Philodemus taught, but it reports debates about sign-inference conducted at Athens ca. 100 BC. Its enormous interest lies partly in the fact that the confrontation between the two schools has led to greater articulation of their respective methodological principles than is found in the work of their third-century BC forerunners. The main views and arguments reported are those of Philodemus’ teacher Zeno of Sidon (ca. 150–75 BC) and of another eminent Epicurean, Demetrius of Laconia (fl. ca. 100 BC), along with the opposing arguments of a certain Dionysius, usually and plausibly held to be the Stoic Dionysius of Cyrene.

In outline, the Epicurean stance is as follows. Signs may be treated indifferently as things or as propositions. For instance, in the inference from the fact of motion to the existence of vacuum, the Epicureans are equally content to say that motion is a sign of void, and that “Since there is motion...” is a sign of “...there is void”. Precision about logical form is not such a matter of concern to them as it is to the Stoics. Although the ‘non-contestation’ requirement is constantly invoked (not usually under that name, however) in their arguments, it is not made as methodologically central as it appears to have been by Epicurus: it merely strengthens inferences whose main basis lies elsewhere. Instead, the fundamental inferential principle is that of ‘similarity’. The basic intuition may be put as follows: if x is similar to y, then, in those aspects in which no relevant difference is found between x and y, what is true of x must also be true of y. One favoured application of this is to inductive inferences, paradigmatically illustrated by the generalisation «all men are mortal». Human beings are alike in species, but differ in numerous other respects, including longevity. However, all human beings on whom information is available have it in common that they are mortal. Systematic study of these facts makes it ‘inconceivable’ that there could be further human beings outside our experience who are immortal. That is, within the human species no difference can be conceived of which would be such as to render any of its members immortal. This kind of similarity is called ‘indiscernibility’ (aparallaxía): in the relevant respects, there is no difference at all between the sign (e.g. the mortality of familiar human beings) and the significate (the mortality of as yet unfamiliar human beings).

The other favoured application of ‘similarity’ is called ‘analogy’, the standard mode of inference for inferring from the macroscopic to the microscopic. Here there are substantial differences, usually of scale, between sign and significate, but ones which leave it still ‘inconceivable’ that what is true of the sign should be false of the significate. A typical use of analogy is the inference of the shape of atoms from the behaviour of similarly-shaped macroscopic bodies. To this position the main Stoic challenge reported by Philodemus is that such inferences could never be cogent. Sign and significate must always differ in some respect if there is to be any purpose in inferring from the one to the other; and any difference at all could in principle turn out to be sufficient to vitiate the comparison. Indeed, it is an observed fact that some things are unique – both unique individuals such as a dwarf in Alexandria said to have had a huge rock-hard head, and unique types such as the lodestone, which alone among stones draws iron, and the square of four, the only square whose perimeter is numerically equal to its area. Therefore we cannot exclude the possibility that the human species contains a unique individual or race which is immortal.

To this the Epicurean reply is that the appeal to unique cases is one which itself relies on the similarity method, thus confirming rather than undermining it (naturally the Stoics could reply that they are using the method purely ad homines). Many valid inductive inferences can be made about unique items. For example, the Epicureans argue, from the uniqueness of the square of four in our world we can infer that it is unique among squares in all other worlds too. This treatment of mathematics on a par with physics is characteristically Epicurean, and it does at least make much sense of their ‘inconceivability’ criterion for similarity inferences. Whether a four-foot square is made of iron, of moonrock or of any other substance, it is ‘inconceivable’ that its mathematical properties should vary, such differences being irrelevant to them. It is the extension of this same principle to cover empirical properties like mortality that underlies the Epicurean similarity method.

Another line of attack by the Stoics is focused on the use of analogy. If analogy proves anything, they argue, it proves too much. For example, from the fact that all macroscopic bodies are coloured and destructible it should be possible to infer that atoms are coloured and destructible. The Epicureans reply that such erroneous conclusions will be avoided by anyone who properly singles out the appropriate level of generality for sign-inferences. From generic properties, only generic properties may be inferred – those without which the kind of item in question becomes inconceivable. Thus (they seem to mean) the only totally generic properties of body will be found to be three-dimensionality and resistance, which can therefore be inferred to recur at the atomic level; colour, on the other hand, is not indissolubly bound to body as such (e.g. air), but only to certain species of body.

The Stoics themselves are reported as endorsing only one form of sign-inference. This is called anaskeué, the ‘elimination method’. The principle is that x is a sign of y only if, by the very fact of the elimination of y, x would be ‘co-eliminated’. It will be seen that this is no more than a special application of the ‘cohesion’ criterion for a sound conditional advocated by Chrysippus (see above). These Stoics, then, are in effect limiting signs to evident facts so related to their significates that a world in which the significate did not obtain would ipso facto be a world in which that evident fact did not obtain either. Arguments from similarity would not obey this requirement. If there turned out to be immortal human beings in an undiscovered country, that would not ipso facto deprive the rest of us of our mortality. However, the Stoics do hold that an acceptable reformulation of the mortality induction is possible: «Since men in our experience are mortal qua men, men everywhere are mortal». Clearly if it were not the case the men everywhere are mortal, the essentialist antecedent, that men in our experience are mortal qua men, would be thereby proven false. Hence the Stoics see themselves as rescuing a logically cogent form of sign-inference, one which even justifies induction, by invoking essences as signs.

Here the Epicureans appear to make a concession. Such inferences are indeed valid sign-inferences, they allow. However, the Stoics have failed to ask how the essentialist premise was itself established in the first place. The answer is that it is the product of protracted and painstaking inductive inference by the similarity method. Only when we have exhaustively studied the resemblances which persist throughout the human race, despite all the accompanying variations, can we infer from these what the essential nature of man consists in, including mortality. That is a sign-inference by similarity, from individual human natures to essential human nature. Once we have completed this induction, and established the essential nature of man, the further sign-inference from the essential mortality of man to the mortality of human beings outside our experience is a trivial, if formally necessary, additional step. The real work of discovery was done in the former stage, by reliance on similarity.

It also become clear why the Epicureans are motivated to make this concession. They cannot deny that some of their favoured sign-inferences fail to fall under the rubric of ‘similarity’. For instance, «Since there is motion, there is vacuum» does not rely on any actual similarity between the sign, motion, and its significate, vacuum. Rather, it is an inference from effect to cause. If then it is to be valid, the Epicureans must admit a second form of sign-inference, and here the elimination method seems to fit their needs. A world from which empty spaces were eliminated would ipso facto be a world in which nothing moved – or so they would maintain. But the acceptance of a role for the elimination method is argued to be no more than a marginal concession. Once again the important question, they insist, is how we establish in the first place that motion always and essentially depends of empty spaces, so that motion without void is inconceivable. And the answer is, once more: by the similarity method. It is by observing all kinds of motion of all kinds of body in all kinds of circumstances that we arrive at the generalisation that, no matter what other aspects may vary, motion essentially depends on empty space. Once we have established this, it becomes a trivial further step to apply it: since there is evidently motion, there must be empty space.

The Epicureans – from whose point of view the debate is reported to us – thus see themselves as the de facto winners. The apparently a priori method of inference which the Stoics declare to be the only valid one has proved to be no more than a trivial adjunct to scientific method. The fundamental process underlying all scientific inference is, rather, that of empirical generalisation.

In the first century BC the philosophical world underwent a radical change. From the 80s onwards, Athens declined as a philosophical centre. The focus moved away from the metropolitan headquarters of the various schools to smaller philosophical groups scattered around the Greco-Roman world, especially in such cultural centres as Rome and Alexandria. By the end of the century, the main concern of philosophers had come to be centred on the study and reinterpretation of the philosophical classics. These were, above all, the works of Plato and Aristotle, although there is no doubt that Stoics continued to study the writings of Zeno and Chrysippus, Epicureans those of the authoritative founders of their own school. The era which followed is loosely characterised as the ‘Middle Platonist’ period (it ends with Plotinus (205-270), who is regarded as inaugurating the succeeding Neoplatonist era). During this period Platonism and Aristotelianism were the dominant schools of thought, but the influence of Hellenistic debate continued to be felt too.

A key figure in this regard is Posidonius (ca. 135-50 BC). Teaching mainly in Rhodes, he was not only the leading Stoic of his day, but also the most important practising scientist that the school ever produced. His investigations spanned all the major branches of mathematics, including astronomy, but he was also known as a passionate inquirer into causes. After studying the Atlantic tides at Cadiz, he was able to confirm and elaborate the earlier thesis of Seleucus that they were influenced causally by the moon, thus fruitfully applying the Stoic doctine of ‘cosmic sympathy’, according to which every part of the world causally interacts with every other part. The standard Stoic formula for the goal of life as «living in agreement with nature» he fleshed out as «living in study of the truth and arrangement of the world, and contributing to it so far as one is able...».

Despite his own commitment to the mathematical sciences, Posidonius was adamant that they are not parts of philosophy, but ancillary disciplines. Even when the philosopher and the astronomer study the very same phenomenon and reach the very same conclusions – for instance that the Earth is spherical or (a special interest of Posidonus’, on which he campaigned against the Epicureans) that the Sun is very large – they proceed in quite different ways. The philosopher demonstrates his truths by starting from the essences and powers of things, or from the goodness of the world, whereas the astronomer’s premises are accidental features of the objects in question - their measured dimensions, speeds etc. Again, the philosopher is concerned to discover causes, whereas the astronomer is more interested in finding one or more hypotheses that will «save the appearances».

Posidonius’ own scientific work imposed on mathematical analyses of cosmic phenomena the philosopher’s concern with the underlying causes, and it is largely this aspect of his work which made it influential in the next two centuries. He is undoubtedly a, if not the, major source for the (largely surviving) Natural questions of Seneca (ca. 1-65 AD), who, unusually for a Stoic of the imperial era, retained an interest in cosmology alongside the now dominant focus on ethics. This treatise is a wide-ranging critical survey of existing theories on individual cosmic phenomena, not heavily dependent on Stoic physical theory or methodology. Like any Stoic, however, he insists that the ultimate value of studying Nature is an ethical one. A scientific writer who is more deeply influenced by Posidonian theory is Cleomedes, whose On the circular motions of the heavenly bodies (of uncertain date, but probably first or second century AD) is a fundamentally Stoic treatment of astronomical and cosmological issues. Finally, it should be noted that two varieties of scepticism kept Hellenistic debates alive in the period 50 BC-200 AD. The New Academy had lost its institutional base at Athens, but we have two powerful spokesmen for it in Cicero (106-43; the works named below were written in 45) and Plutarch (fl. 80-120 AD).

Cicero’s De natura deorum engineers a debate between Epicureans, Stoics and their Academic critics on central questions of theology. Cicero himself judges Stoic theology probable but unprovable, and when speaking in a sceptical voice at Academica (II, 110-128) he criticises those who adopt doctrinal stances in epistemology and physics, by the device of systematically exposing conflicts between the major thinkers on every issue, demanding to know how we can ever know which to believe. As for Plutarch, he is himself a Platonist, developing his own original interpretations of Plato’s doctrines regarding the world soul and related issues. But he is also, in allegiance, an ‘Academic’, meaning a follower of the Hellenistic New Academy, and among his most important works are critiques of Epicurean and Stoic doctrine. His On Stoic self-contradictions alleges a series of contradictions between or within single tenets of classical Stoicism, and On common notions attacks the Stoics for violating the ‘common notions’ (equivalent to próläpsis) which they claim to make the basis of their own epistemology.

In the mean time Pyrrhonism, refounded by Aenesidemus in the first century BC, was becoming the dominant form of scepticism, and the surviving writings of Sextus Empiricus (second century AD) take Stoicism as their leading target. Books VII and VIII of his Adversus mathematicos attack the principles of Stoic scientific inference, and Books IX and X contain a systematic critique of Stoic physics. In a series of separate treatises, he also attacks the foundations of the individual sciences (Against the geometers, Against the arithmeticians, Against the astrologers, and Against the musicians).

David Sedley

References

- Algra 1995: Algra, Keimpe, Concepts of space in Greek thought, Leiden-New York, E.J. Brill, 1995.

- Asmis 1984: Asmis, Elizabeth, Epicurus’ scientific method, Ithaca (N.Y.), Cornell University Press, 1984.

- Barnes 1982: Sciences and speculation. Studies in hellenistic theory and practice, edited by Jonathan Barnes [et al.], Cambridge-New York, Cambridge University Press; Paris, Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme, 1982.

- Dragona-Monachou 1976: Dragona-Monachou, Myrto, The stoic arguments for the existence and the providence of the gods, Athens, National and Capodistrian University of Athens, Faculty of arts, 1976.

- Ebert 1987: Ebert, Theodor, The origin of the Stoic theory of signs in Sextus Empiricus, “Oxford studies in ancient philosophy”, 5, 1987, pp. 83-126.

- Flashar 1994: Die Philosophie der Antike, hrsg. von Hellmut Flashar, Basel, Schwabe, 1983-1994, 4 v.; v. IV: Die hellenistische Philosophie, 1994.

- Frede 1974: Frede, Michael, Die stoische Logik, Göttingen, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1974.

- Giannantoni 1996: Epicureismo greco e romano, a cura di Gabriele Giannantoni e Marcello Gigante, Napoli, Bibliopolis, 1996, 3 v.

- Kidd 1978: Kidd, Ian, Philosophy and science in Posidonius, “Antike und Abendland”, 24, 1978, pp. 7-15.

- Kneale 1962: Kneale, William Calvert - Kneale, Martha, The development of logic, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1962.

- Long 1974: Long, Anthony A., Hellenistic philosophy. Stoics, Epicureans, Sceptics, London, Duckworth, 1974.

- — 1987: Long, Anthony A. - Sedley, David N., The hellenistic philosophers, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1987, 2 v.

- Manetti 1987: Manetti, Giovanni, Le teorie del segno nell’antichità classica, Milano, Bompiani, 1987.

- — 1996: Knowledge through signs: ancient semeiotic theories and practices, edited by Giovanni Manetti, Turnhout, Brepols, 1996.

- Pohlenz 1948-49: Pohlenz, Max, Die Stoa. Geschichte einer geistigen Bewegung, 5. Aufl., Göttingen, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1948-1949, 1978-1980, 2 v.

- Sambursky 1959: Sambursky, Samuel, Physics of the Stoics, London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1959.

- Schofield 1980: Doubt and dogmatism. Studies in hellenistic epistemology, edited by Malcolm Schofield, Myles Burnyeat, Jonathan Barnes, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1980.

- Sedley 1976: Sedley, David, Epicurus and the mathematicians of Cyzicus, “Cronache ercolanesi”, 6, 1976, pp. 23-54.

- — 1982: Sedley, David, On signs, in: Science and speculation. Studies in hellenistic theory and practice, edited by Jonathan Barnes [et al.], Cambridge-New York, Cambridge University Press; Paris, Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme, 1982, pp. 239-272.

- Solmsen 1961: Solmsen, Friedrich, Greek philosophy and the discovery of the nerves, “Museum Helveticum”, 18, 1961, pp. 150-197; ora in: Solmsen, Friedrich, Kleine Schriften, Hildesheim, G. Olms, 1968, 3 v.; v. I, pp. 536-582.